Web scraping 50 thousand documents from different sources for NLP

In following article we will explore methods of building your own dataset for NLP. Doing so from ground up means solving a lot of problems. Publicly available datasets (ie. Kaggle) are usually preprocessed, where NaN values are properly tagged and out-of-category rows are removed. That is not the case when you start with empty spreadsheet which you will want to populate with data straight from the source. By source I don’t mean API which responds with nicely formated JSON key value pairs. We will learn how to get data directly from the websites, store it and clean it properly while avoiding unneeded losses. In part II we will continue with NLP methods of exploration. Building dataset yourself shows importance (and hardships) of data cleaning. You will discover how much better understanding of your data you will have after knowing what to remove from it and how to judge what to remove.

Why read it?(TL;DR)

It’s a long article, is there anything you didn’t see before? Well, I hope so. This article is more about logic and design of large data project which we will build step-by-step than a showcase of tools and methods used. We will dive into code of course (that is a big part of this text!) but reality is that code is written fast when you already know what to write. Here we will ponder on ‘what to write’ not, ‘how to write it’.

Table of Contents:

- Introduction: What topic to choose for data science project?

- Finding source of data (for free).

- Web scraping using WaybackMachine (web.archive.org)

- Web scraping full html pages based on condition.

- Extracting privacy policy text from 50.000 urls.

- Storing scrapy items in PostgreSQL

- How to clean textual data using python?

- Summary

Tools used: Scrapy, PostgreSQL, Pandas, Matplotlib, NLTK, Regex, SQLalchemy, numpy

Introduction: What topic to choose for data science project?

As mentioned, we will not work with any public API, nor we will work with something which was already described numerous times – I am looking at you, real estate data. It’s not that this is not interesting, you can find a lot of fresh case studies build around popular topics like housing markets or macroeconomic indicators. But here, let’s use something else.

We will build a large corpus of legal documents which are available on almost every website. Namely, privacy policies & terms of service. If you are interested in how to gather large amount of specific data from many different websites by web scraping – this is exactly what we will do. To accomplish this, I needed to hack around with few methods as you cannot crawl Google.com effectively without large resources. You also want to avoid falling into grey area of web scraping or wasting a lot of time for manual discovery of data sources. We want to save time, build original dataset, clean it and learn something new. Let’s start.

Finding source of data (for free).

One rule will guide us through process of finding our source – Whatever was posted on a web, stays on a web.

There are two services which are actually dealing with privacy policies and their analysis. I recommend checking out both, a lot of work went into those projects and they deserve community appriciation.

https://pribot.org/polisis – Summarization of privacy polices using ML.

https://tosdr.org/ - Rating of privacy policies using manual review.

TOSDR processed more than 500 pages in manual manner, describing in detail crucial parts of those texts.

PRIBOT uses different approach, “At the core of Polisis is a privacy-centric language model, built with 130K privacy policies, and a novel hierarchy of neural-network classifiers that accounts for both high-level aspects and fine-grained details of privacy practices.”

(Read more here: https://pribot.org/files/Polisis_USENIX_Security_Paper.pdf)

End product of this article is around 50.000 documents stored in database. How can we get it?

Idea 1. Find multiple sources manually.

Idea 2. Scrape Google for keywords and then websites.

Idea 3. Find a resource which allows you to get 50.000 thematic websites.

We can grade those ideas by time/effort/resources ratio needed to make them work. Idea 1 is most accurate, it will find you websites you actually want to look at, great if you are building a product around specific dataset. Yet, it will be slow and highly curated process. Idea 2 is a grey area of web scraping, companies do it, employing a lot of resources to build distributed crawlers and hide their activity from Google which heavily dislikes such practices. It was (is?) very popular in SEO community. Idea 3 is what we plan to do. The bottleneck is lack of free resource with quality websites to scrape from.

There is also additional constrain, we want to have policies from websites that ‘matter’. So anything which stores user information, has considerable volume of traffic, provides some sort of a service to Internet buyers or has high position in rankings. That way we can be sure that contents of policies do matter for large amount of users. Also, we will focus on English-only websites.

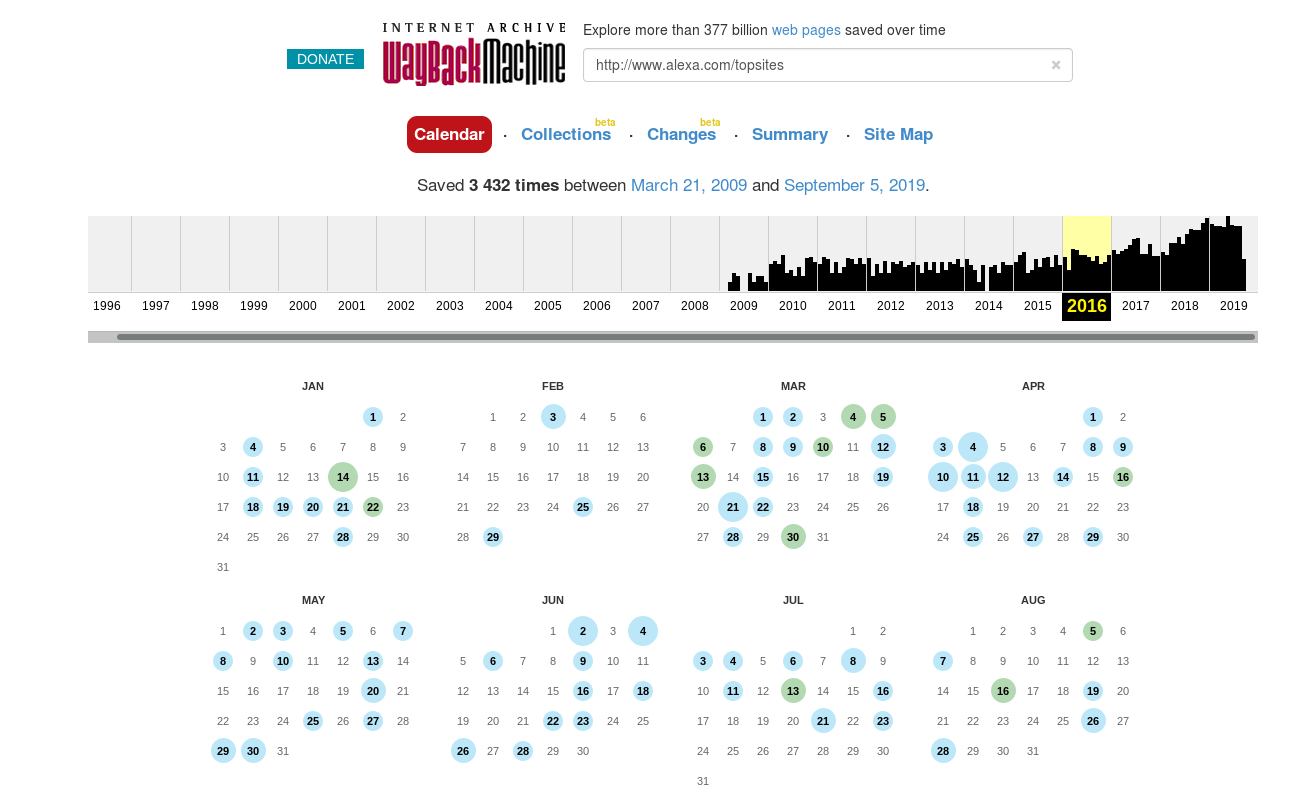

Alexa was providing “top websites globally” service for free few years back, but not anymore. It’s a shame because their list allowed for searching by country or categories, exactly what we needed. I am not interested in specific websites statistics, I am only interested in URL to website, however Alexa pushes me to pay for the whole service. What can be done about it?

Well, we can check previous, free, version of Alexa using https://web.archive.org/.

Bingo, version from 3 years ago is still free and archive.org created snapshots!

Yes, this will not be perfectly accurate, but a lot of websites existing in second half of 2016 still exists today and their importance didn’t change much. Alexa ranking do not necessarily reflect importance of given website for global Internet traffic but it will be good approximation when it comes to finding ‘websites that matter’.

Web scraping using WaybackMachine (web.archive.org)

After entering todays Alexa URL, we get following link to scrape from:

https://web.archive.org/web/20161118212145/http://www.alexa.com/topsites/category

We need to crawl every category (and sub-category or even sub-sub-category!) and every page in this category to find URLs leading us directly to websites. Unfortunately, alexa doesn’t provide direct link to website anywhere on its page! No worries, we will use website titles and just add necessary ‘https://’ prefix after using a little bit of python magic and our very first ‘cleaning’ code.

Full code of this web crawler can be found here: https://github.com/neotokio/scrapy_spiders/tree/master/get_policies/alexachive

Step-by-Step explanation:

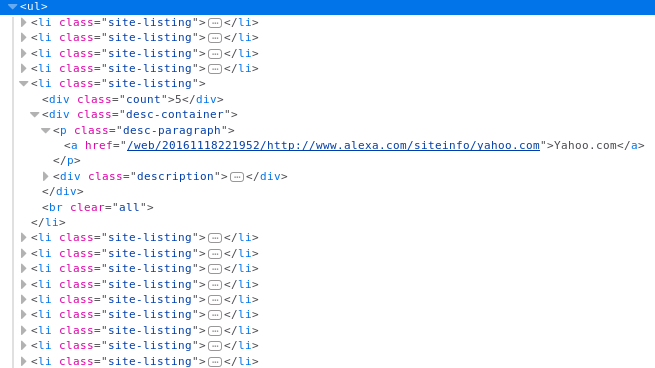

Restrict LinkExtractor paths to only /ul element where website name (we will make it into url later) is found.

rules = (

Rule(LinkExtractor(restrict_xpaths=('//div[@id="subcat_div"]//ul'),),

callback="parse",

follow=True),)Iterate over each </a href/> element containing internal link to more detailed statistics of given website. It’s also visible on screenshot from inspection tool. We need to grab all URLs like this, after this we pass it to content function.

</a href/=”/web/20161118221952/http://www.alexa.com/siteinfo/yahoo.com”>Yahoo.com</a>

def parse(self, response):

links = response.xpath('//div[@id="subcat_div"]//ul//a[contains(@href, "web")]//@href').extract()

for link in links:

url = urljoin(response.url, link)

yield scrapy.Request(url, callback=self.content)We extract necessary items using Xpath. item[‘url’] is from where we will build actual URL (using title + ‘http:// prefix) to website after.

def content(self, response):

item = AlexachiveItem()

item['category'] = response.xpath('//span[@class="page-title-text"]//a//text()').extract()

for items in response.xpath('.//section[@class="td col-r"]//ul//li'):

item['url'] = items.xpath('.//a[contains(@href, "web")]//@href').extract()

item['description'] = items.xpath('.//div[@class="description"]//text()').extract()

yield itemNow we have .csv file with URLs in following format:

/web/20161118221952/http://www.alexa.com/siteinfo/yahoo.com

/web/20161118221952/http://www.alexa.com/siteinfo/google.com

/web/20161118221952/http://www.alexa.com/siteinfo/twitter.comWhat we want to have is:

https://yahoo.com

https://google.com

https://twitter.comLet’s start cleaning those strings from unnecessary characters. We want to save just last part of it.

df = pd.read_csv('/home/user/Scrapy/AlexaPart2.csv')

categories = df[df['description'].isna()]

df = df[~df['description'].isna()]

df['url'] = df.url.str.replace(r'/web/\d+/http://www.alexa.com/siteinfo/',' ')

df['url'] = df.url.str.replace(r'/\w+/\S.+|/~+.\w+/\S+', '')

http_series = df.url[df.url.str.contains('http')]

df['url'].drop_duplicates(inplace=True)

df['url'] = df.url[~df.url.str.contains('http')]

df['url'] = 'http://' + df['url']

df['url'] = df['url'].str.replace(' ','')

full_series = df.url.append(http_series, ignore_index=True)

df_more_description = df[df['description'].str.contains('More')]

df['description'] = df['description'].str.replace(r',…,More,', ' ')

full_series.dropna(inplace=True)

full_series.drop_duplicates(inplace=True)

full_series.to_csv('/home/user/Scrapy/AlexaPart2_processed.csv', index=False)Step-by-step explanation:

- Read .csv file with data.

- Select all rows which do not have empty description

- Replace string /web/20161118221952/http://www.alexa.com/siteinfo/ using regex with nothing

- Replace any edge-cases with nothing (ie. subdomains)

- Save websites containing ‘http’ to separate variable (some of titles do contain it!)

- Drop duplicate entries

- Select urls not containing ‘http’.

- Add ‘http’ to those.

- Remove unnecessary spaces

- Merge urls with added ‘http’ prefix with ones which already had one.

- Remove unnecessary strings from description item.

- Drop empty and duplicated rows and save to .csv (we save without index because we need to use those URLS for further scraping! Scrapy will not read those with numeric index at the begining)

Ready, now we have 50.000 URLS to scrape privacy policies from!

Web scraping full html pages based on condition.

We have a list of 50.000 urls in format of http://example.com. We need to find link to privacy policies in each of those websites.

A lot of websites follow a pattern of having url in form of :

http://example.com/privacy-policy

http://example.com/privacyBut very often there are unforeseeable complications, for example:

http://example.com/legal/docs/privacy-policy – When URL is hidden within additional directory.

http://us.example.com/privacy-policy – When it redirects to geolocated services.

http://docs.example.com/privacy - Has separate subdomain for legal documents.It was also often a case that policy is split into many separate documents, each detailing data usage for specific context.

Our main interest right now is privacy policy & terms of service documents, however, we will also store urls to other kinds of documents which do not (most likley) fit that pattern (for example, cookies related documents). It’s always a good practice to save potentially important information, even if we cannot use it at current moment, especially when it doesn’t cost us anything in terms of additional code or time of execution.

Extracting privacy policy text from 50.000 urls.

Full code of this web crawler can be found here: https://github.com/neotokio/scrapy_spiders/tree/master/get_policies/getpolicy

Let’s work logic of this web crawler step-by-step:

Restrict following links to avoid deep crawl through the whole web page. We want just one page. Looping over so many internal urls in search of privacy policy is pointless. If you will manually visit few of links you notice that privacy policies are almost always at front page.

rules = (

Rule(

LinkExtractor(),

callback='parse', follow=False),)Read urls from start_urls (this is where we load .csv file with 50k links to crawl). Yield request to each url specifying another function as callback (parse).

def start_requests(self):

for url in self.start_urls:

yield scrapy.Request(url, callback=self.parse, meta={'download_timeout': 5}, errback=self.errback_f)This function handles all of our web crawling. First, it looks for string ‘privacy’ within each response.url (full code looks also for ‘terms’). Looking in response.body is another, viable option, but we save some time by checking just url. Else condition is to catch all of the exceptions from this and store it in separate item, this entries will be reprocessed later together with whatever errback_f function catches. Most important part of parse function is xpath which extracts raw text of documents from html source code with as little unnecessary information as possible. This deserves additional explanation in point below.

def parse(self, response):

if 'privacy' in response.url:

item = GetpolicyItem()

raw_policy = response.xpath(

"//*[contains(text(), 'Policy') or contains(text(), 'Privacy')]"

"/following-sibling::*[not(self::script)][not(self::meta)][not(self::link)]//text()").extract()

catch_regex = response.url

domain = re.sub(r'/\w+/\S.+|/~+.\w+/\S+', '', catch_regex)

item['domain'] = domain

item['url'] = response.url

item['privacy'] = raw_policy

else:

item = GetpolicyItem()

item['rest_url'] = response.url

catch_regex = response.url

domain = re.sub(r'/\w+/\S.+|/~+.\w+/\S+', '', catch_regex)

item['domain'] = domain

yield itemIt is problematic to process text from html while leaving unnecessary characters/syntax out. We can use Beautiful Soup parser (we actually do use it later), but a lot of websites behave in unexpected manner and parser still includes script or meta tags. I opted for trying to limit what exactly do I want to ‘catch’ by conditions within my xpath. After visiting http://example.com/privacy-policy xpath will look for any text containing ‘Policy’ or ‘Privacy’. This will happen in first come, first served basis, exactly what I want as almost all of policies state this particular string at the beginning of the document, usually somewhere between title or h1 tag. After that it will catch all of the text below this condition, excluding script, meta and link tags. About 60% of our documents are ‘NLP ready’ being caught by this xpath, remaining 40% need further processing.

raw_policy = response.xpath(

"//*[contains(text(), 'Policy') or contains(text(), 'Privacy')]"

"/following-sibling::*[not(self::script)][not(self::meta)][not(self::link)]//text()").extract()Errback_f handles all of our timeouts and another set of urls for further processing.

def errback_f(self, failure):

if failure.check(TimeoutError):

request = failure.request

item = GetpolicyItem()

item['url'] = request.url

item['fail'] = 'FAIL'

yield itemWe could chain this two crawlers into one (crawling links from alexa and navigating to privacy policy), without a need to read and parse urls from .csv file and separate execution. It didn’t happen because figuring out best way to catch a lot of documents from a lot of different websites it’s hard to debug and optimize! Running such crawler takes time, running it on chunks of data will not work too well because those chunks do not paint a full picture, NaNs are of least concern here, but ‘garbage text’ is a big problem– this ‘garbage’ is unique so it’s hard to catch, problems pile up very fast and because this is ‘long’ data we end up with very big database full of, most probably, garbage. I’ve choose to work in steps, ‘have a peak inside’, evaluate given approach, implement adjustments and execute only then. This involved a lot of back-and-forward with code and at least few compromises. Sometimes it’s just easier to move ‘outliers’ for later processing than try to catch all of data at one pass.

Storing scrapy items in PostgreSQL

Another crucial decision was how to store scraped documents. For purely quantitative data, usually the best choice is .csv file, here I opted for storing data in postgres, another interesting choice would be ElasticSearch allowing to search by text, but for now let’s focus on how to connect scrapy with postgres.

Begin by installing postgres and creating database. To create database you need to specify it’s name, user, password, table name and grant necessary privileges. All of those steps are required to pipeline scrapy items into postgres, without it connection will fail. We create it by issuing following commands in psql shell (postgres interactive shell):

Connect to shell (as postgres user):

sudo -u postgres psqlCreate database:

create database gp_db;

create user gp_user with password 'testpass1';

grant all privileges on database privacy_process to gp_user;Now, connect to your database shell:

/c gp_db;Create table:

/c crawl

CREATE TABLE policy (

id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

url TEXT,

fail TEXT,

title TEXT,

text TEXT

);We specify every type as TEXT without limits because it is impossible to judge how long each document will be. Remember to end all of your commands with semicolon, otherwise postgres command will not execute. Scrapy requires password for user account, otherwise it will refuse to connect. If you run into problems with privileges you can add them manually, by issuing following commands:

GRANT ALL PRIVILEGES ON DATABASE gp_db TO gp_user;

GRANT ALL PRIVILEGES ON TABLE policy TO gp_user;

GRANT ALL PRIVILEGES ON ALL TABLES IN SCHEMA public TO gp_user;

GRANT ALL PRIVILEGES ON ALL SEQUENCES IN SCHEMA public TO gp_user;

GRANT ALL PRIVILEGES ON ALL FUNCTIONS IN SCHEMA public TO gp_user;Scrapy item pipeline to postgres

There are multiple ways to connect scrapy with postgres. Here we will use sqlalchemy, I opted for sqlalchemy mostly because it’s easiest and error reporting is on high level (contrary to setting up pipeline only with psycog which throws pretty enigmatic error messages even for most obvious things).

Adjust your settings.py file inside of spider directory

DATABASE = {

'drivername':'postgres',

'host':'localhost',

'port':'5432',

'username':'gp_user',

'password':'test1',

'database':'gp_db'

}Create models.py file inside of spider directory (same place where settings.py resides)

from sqlalchemy.engine.url import URL

from sqlalchemy.ext.declarative import declarative_base

from sqlalchemy import create_engine, Column, Integer, String, DateTime

from sqlalchemy import (

Integer, SmallInteger, String, Date, DateTime, Float, Boolean, Text, LargeBinary)

from getpolicy import settings

DeclarativeBase = declarative_base()

def db_connect():

"""

Performs database connection using database settings from settings.py.

Returns sqlalchemy engine instance

"""

return create_engine(URL(**settings.DATABASE))

def create_table(engine):

DeclarativeBase.metadata.create_all(engine)

class Deals(DeclarativeBase):

"""Sqlalchemy deals model"""

__tablename__ = "scraped"

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True)

privacy = Column('privacy', Text)

terms = Column('terms', Text)

rest_url = Column('rest_url', Text)

url = Column('url', Text)

fail = Column('fail', Text)

domain = Column('domain', Text)It’s a nice snippet take from: https://newcoder.io/scrape/part-3/ I recommend whole tutorial if you are new to scrapy, it’s a well written guide. I will skip explaining what each function does (you can read it on newcoder.io), the only important part for our project is mapping of columns in class Deals. Those variables need to correspond to the ones you created earlier while setting up database and table, names are case sensitive and types need to be the same.

Change pipelines.py

from sqlalchemy.orm import sessionmaker

from getpolicy.models import Deals, db_connect, create_table

class GetpolicyPipeline(object):

def process_item(self, item, spider):

return item

def __init__(self):

engine = db_connect()

create_table(engine)

self.Session = sessionmaker(bind=engine)

def process_item(self, item, spider):

session = self.Session()

deal = Deals(**item)

try:

session.add(deal)

session.commit()

except:

session.rollback()

raise

finally:

session.close()

return itemNow we can run our spider, it should save items to postgres. We check it by login into psql shell and to our database (/c gp_db) to issue following command:

select * from table limit 5;

It will select all columns for first 5 rows.Remember that running scrapy multiple times will append items to database. If you want to start with clean database for each run of spider you need to issue following command in psql shell:

TRUNCATE table_name;

DELETE FROM table_name;How to clean textual data using python?

Full code here: https://github.com/neotokio/scrapy_spiders/blob/master/get_policies/getpolicy/getpolicy/spiders/svd_processing.py

We have our database ready, spider gathered a lot of data and stored it in sql database. Now it’s time to process this data. We need to delete unwanted characters from scraped html pages. However, after quick glance at data we notice that a lot of documents are polluted with many different cases without any obvious pattern. First we need to understand structure of our out-of-order data to know what exactly do we want to remove.

Average length of privacy policy is 6-8 thousand characters. We cannot look at this data comfortably using pandas head() function. We store close to 50 thousand of separate documents, each one of them contain a lot of noise. We need to setup some framework for grading those documents:

- Check length of each document. Remove any document with length shorter than 1500 characters

- Check if specific string exists in document.

Checking for length guarantees that we deal with properly downloaded html page, there are a lot of cases when we downloaded just part of document (ie. javascript heavy websites) or document without policy text at all! Second condition checks for existence of specific css syntax. It seems that parsers very often catch css as part of text, no matter what we do – we will want to get rid of it without deleting actual text.

privacy_css = privacy_only[privacy_only['privacy'].str.contains('inline|font|img|margin|px|padding|menu')]

privacy_only = privacy_only[~privacy_only['privacy'].str.contains('inline|font|img|margin|px|padding|menu')]

privacy_only = privacy_only[privacy_only['privacy'].str.len() > 1000]

privacy_css = privacy_css[privacy_css['privacy'].str.len() > 1000]We divide our dataset in two dataframes, one with documents heavy on css syntax inside and second one free of those. We will use a slightly different functions to clean them so we need to have them available separately. This is because regex substitution can have different effects depending on order of execution.

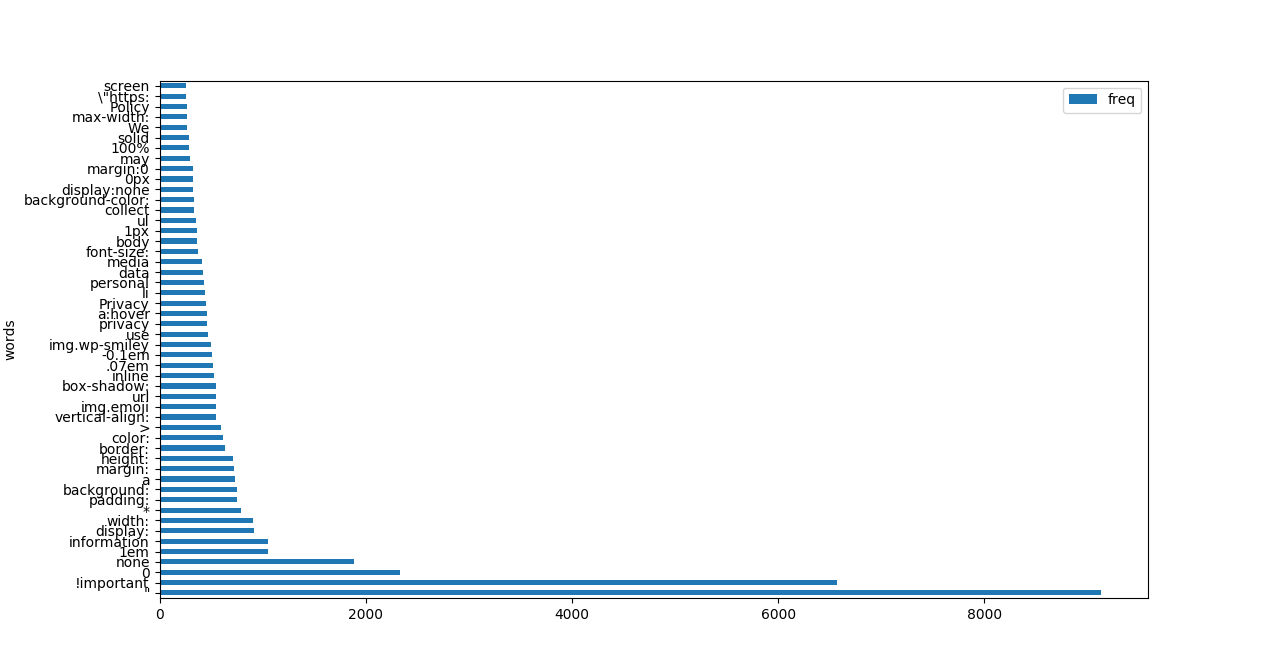

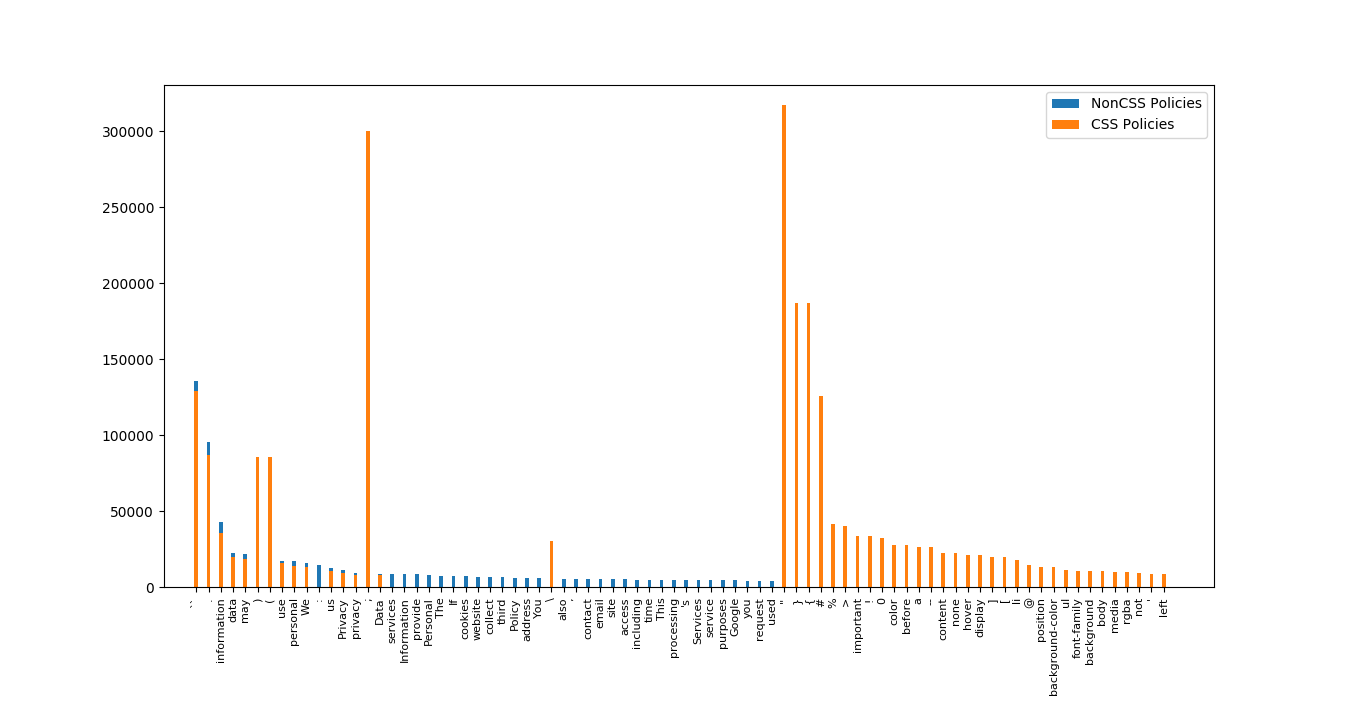

How did we decide on which tags to look for? We created word frequency count for unprocessed documents checking first 100 characters only (assumption is that css is always in beginning of the document). We could add more of those tags but this is enough to deal with most of cases we are interested in.

Above plot shows word count for unprocessed documents, later we will recreate it for processed documents to show difference. In top 50 words we can see a lot of non-alphanumeric characters and a lot of css syntax. Using word frequency is a good way to get a ‘skim’ at data we are working with. Remember to remove stopwords and flatten your word list! ‘Flattening’ refers to concating all of strings from all documents into one list, without it we cannot use Counter function. Here’s code:

first_100 = privacy_css.apply(lambda x: x.str.split().str[0:100])

first_100 = first_100['privacy']

css_flat = []

for word in first_100:

for item in word:

css_flat.append(item)

count = Counter(css_flat).most_common(50)

plot_df = pd.DataFrame(count, columns=['words', 'freq'])

plot_df.plot(kind='barh', x='words')Let’s move to actual cleaning of documents. We already store them in separate variables. The biggest challenge is properly cleaning css tags without removing text. Stopwords and non-alphanumeric signs (excluding punctuation for now!) are secondary task. While working with re library it is however important to notice that execution of one substitution can change, or even make impossible, another one, some regex depends on existence of specific characters, for example – dots. We need to think what to remove first not to end up in a loop without option to ‘hook’ our regex to anything useful. We apply function to all of our pandas column in following way:

privacy_css['privacy'] = privacy_css['privacy'].apply(clean_css)We define clean_css function and compile necessary regex before:

BAD_1 = re.compile('[^0-9A-Za-z #+_,.]') # Remove everything which is NOT [] - add ., if You want to keep punctuation

HASH_REMOVE = re.compile('#\S+') # Remove any word with hash in front

DIGIT_REMOVE = re.compile('\d\w*') # Remove any word with digit

FIRST_CSS = re.compile('[\#\.\w\-\,\s\n\r\t:]+(?=\s*\{)') #Remove css tags

CSS_TAG2 = re.compile('.*;') #Remove remaining css tags

JS_RM = re.compile('/\**.*\/') #Remove css tags between slashes

SPACES = re.compile('\s\s+') #Remove double spaces

STOPWORDS = set(stopwords.words('english')) # Remove stopwordsdef clean_css(text):

text = BeautifulSoup(text, "lxml").text

text = CSS_TAG2.sub(' ', text)

text = FIRST_CSS.sub(' ', text)

text = JS_RM.sub(' ', text)

text = HASH_REMOVE.sub(' ', text)

text = DIGIT_REMOVE.sub(' ', text)

text = BAD_1.sub(' ', text)

text = SPACES.sub(' ', text)

text = ' '.join(word for word in text.split() if word not in STOPWORDS)

return textFunction for cleaning documents without css tags is slightly different. Remember, order matters!

def clean_noncss(text):

text = BeautifulSoup(text, "lxml").text

text = CSS_TAG2.sub(' ', text)

text = FIRST_CSS.sub(' ', text)

text = BAD_1.sub(' ', text)

text = SPACES.sub(' ', text)

#text = ' '.join(word for word in text.split() if word not in STOPWORDS)

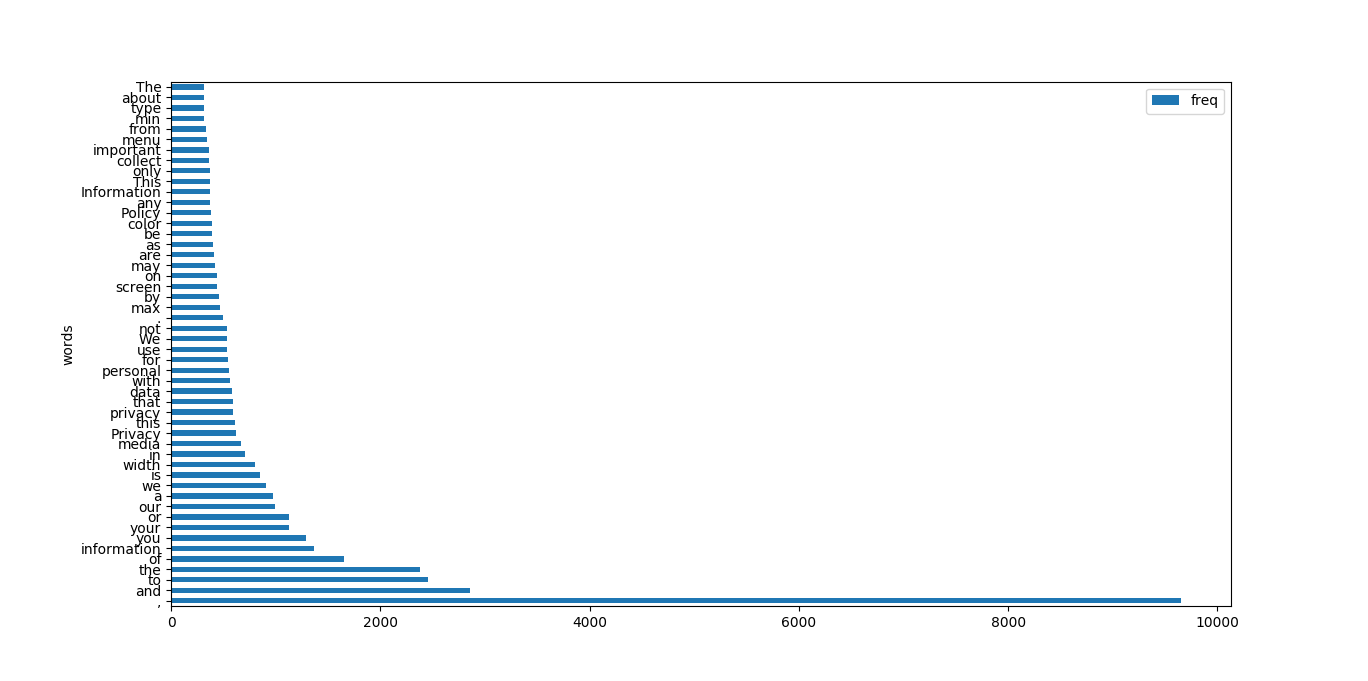

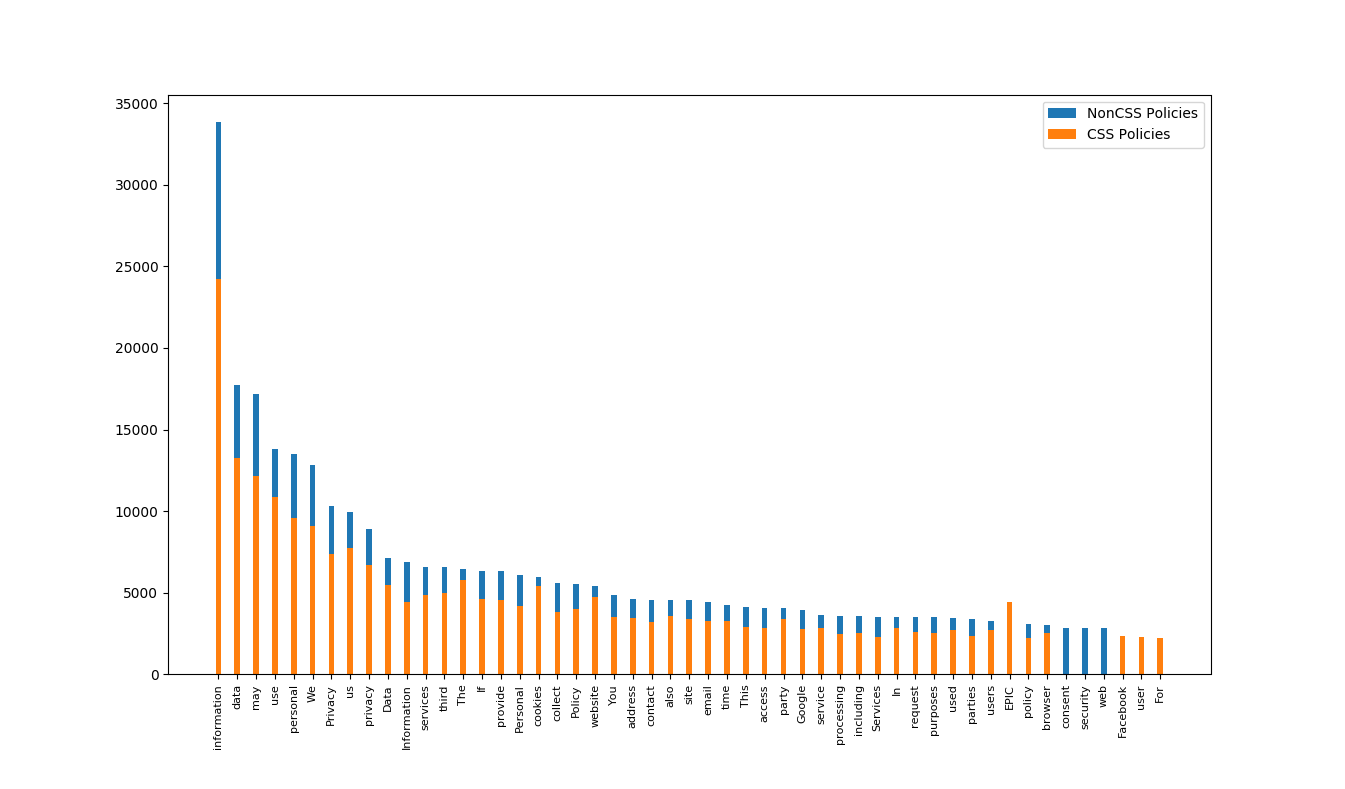

return textWe concat both dataframes (css-heavy and non-css heavy) back into one dataframe. Let’s check how word frequency for first 100 strings looks now.

We still have some leftover tags, but it’s far better, we can see that word distribution is more natural. This should not influence further exploration of this dataset and should allow for building some good models.

To actually compare how well of a job we did with cleaning css syntax let’s create stacked bar chart comparing non-css and css documents. They should have very similar word distribution.

Unprocessed documents plot followed very specific distribution:

While processed documents plot is much different:

As we can see, non-alphanumeric characters and css syntax is no longer prevailing theme. Because CSS heavy documents were a smaller dataset they are lower in overall count, but beyond that we can see that distributions are very similar. We can conclude that text cleaning was successful.

Summary

After finishing all of the above steps we have a corpus of 50 thousand documents stored in postgres database. All of those are cleaned from unwanted characters and badly formated text. We used pretty simple techniques for this but, nevertheless, very effective.

In process of searching for possible solutions we encountered few others very good propositions of exploring such big body of documents and cleaning them effectively. For my purposes, regex was sufficient. However, this is not production ready dataset, it could still be processed more, for example:

- Creating a full dictionary of characters to remove, tokenizing it and running compare with documents we have – sort of a ‘brute force’ solution.

- Building TD-IDF index of all documents and using is as a statistical guide for removal of unwanted characters.

- Using ML solutions, assuming similarity of documents.

Regex was a method of choice because of it’s simplicity and amount of time needed to make it work.

Web scraping from Alexa was personal choice. As mentioned, we could easily do with just manually adding different data sources to achieve same effect. Alexa provided us with a short cut and also shown alternative way to scrape websites. Please, set your crawler settings for appropriate timeouts using web.archive.org for crawling, all of requests will pass through their servers!

In Part II we will use NLP to understand all of our documents better.